PBA TECH TALK - Norm Duke

PBA TECH TALK by Ted Thompson

BOWLING Magazine July 2002

Reprinted with permission from the USBC

Sticking to established Ball Layout Parameters helps Duke Maximize his Natural Abilities

In the last “PBA Tech Talk", we featured Walter Ray Williams Jr., a player who doesn’t really concern himself with the technical “mumbo jumbo” of bowling ball dynamics. This time, we’re featuring Norm Duke as another player who drills a lot of balls throughout the year, but also remains pretty conservative in his choice of layouts.

There are a lot of bowling fans who believe the professionals use every ball-drilling trick in the book to knock down pins. While that may be true for a handful of players, most of the Professional Bowlers Association’s top players use pretty basic layouts and make adjustments using their talent. Duke is one of the latter types of players and his credentials speak loudly.

Norm Duke has been PBA Player of the Year twice. The first time, in 1994, he predominately used a ball (Columbia Beast) that had fairly low differential and, therefore, was a ball that he could manipulate using physical adjustments to get the reactions he wanted. When he won Player of the Year honors again in 2000, Duke predominately used the AMF Menace Tour (actually a dark-colored Columbia Pulse). This was also a low flare ball and he again used his physical talents to make lane adjustments.

Unfortunately for Duke, technology changes so fast these days that this type of ball did not work very well with the new “slicker” oils that came into use on the PBA Tour during the 2001-02 season. Basically, the cover stock was not strong enough to grip the lane and Duke had to search for “another look.” Duke experimented more during the 2001 season with different layouts and types of balls than he had in years, but he also stayed within his philosophies. One thing that Duke does not change is his grip. Most of the top players don’t change grip very often. Duke uses a standard fingertip grip with a couple of idiosyncrasies that separate him from others.

The first thing you might notice when looking at one of Duke’s balls is the shape of his thumbhole. He begins by drilling a 15/16 or 61/64 size pilot hole, depending on the swelling of his thumb at the time, and then “notches” it out with a 23/32 end mill to a side-to-side measurement of .986" at 38 1⁄2 degrees. Duke uses the sharp edge created by the notch to hang onto the ball during his swing. He will also use a cork insert in the front of the thumbhole for added texture to ensure a solid grip in the ball. Duke also places white tape behind the cork insert and adds and removes pieces of tape to adjust the size of the hole during competition. He places small strips of white tape into and out of the notch to adjust the size of the hole. If you ever see Duke on TV “fiddling” with his thumbhole, this is what he is doing. A professional is always trying to get that perfect feel and some players are more sensitive than others. Duke is one of the more sensitive players on the PBA Tour.

Duke uses very little bevel in all of his gripping holes. This lack of bevel keeps the ball hanging onto his hand with minimal grip pressure. I would say his finger holes are some of the least-beveled on the tour today. He also uses zero lateral (left or right) pitch in his thumbhole. This “zero pitch” in his thumbhole enables him to either release the ball in a “thumb down or thumb out” position. If the lanes call for a delayed reaction, Duke will spin the ball or lower his roll, by rotating his thumb down at the release point. If he is trying to roll the ball end over end, Duke will keep his “thumb out” or right of 12 o’clock at the release point. This release will enable the ball to read the lane sooner.

If Duke were to use either right or left pitch in his thumbhole, it would limit his release options to the characteristics produced by right and left pitches. In theory, right pitch promotes a “thumb down” release where left pitch promotes a “thumb out” release.

When Duke is in the PBA Mobile Service Center drilling balls for a particular block or condition, he will lay out all of his balls in a way he describes as “inside the box.” Duke has a limit on how strong or how weak he will lay out a ball and he won’t go “outside this box.” Why? Because he wants to be able to throw the ball any way he sees fit not only during the course of a tournament, but also during the course of a block or even a game at times. By using layouts that stay within these limits, Duke feels he is not limited in his choices of deliveries with any particular ball.

Duke’s limit for a weak layout or when he wants to “minimize a weight block’s imbalance” is on the vertical centerline of his grip, usually above the finger holes. This would place the pin about 6 1⁄2" from his positive axis point.

His limit for a strong layout is “shorter and stronger” or maximum leverage which puts the pin 3 3⁄8" from his positive axis point. Duke will lay out all of his equipment between these two parameters. If Duke is looking for a stronger or weaker reaction, he would rather make adjustments with cover stocks than with excessive pin placements, especially if he is trying to weaken his reaction.

Another constant in Duke’s choice of layouts is that he will almost exclusively use an extra hole. Usually he will place the extra hole on his PAP. The extra hole, Duke says, “livens up the overall ball reaction for him” and gives him a look he can read and use to make adjustments.

Norm Duke has built his game, grip and layout philosophy around one premise: versatility. He is arguably the most versatile player in bowling history. He has won 19 PBA titles plus the 1993 ABC Masters by “hooking the whole lane", "piping it to the pocket", "playing the twig” and everywhere in between.

Even though he failed to win a PBA title during the extended 2001-02 PBA season, he did cash in 26 of 30 events and ranked ninth in average. A testament to his ability was his induction into the ABC Hall of Fame in 2002.

By keeping his layouts within known constants, Duke can make the necessary adjustments the way that works best for him — with his physical talent. ■ Bowling July 2002

PBA TECH TALK - Walter Ray Williams Jr.

PBA TECH TALK with Ted Thompson

BOWLING Magazine May 2002

Reprinted with permission from the USBC

Basic grip, cover stock management are keys to Williams’ 15 years of PBA dominance

Walter Ray Williams Jr. arguably has been the most dominant bowler over the last 15 years. Over that span of years, Williams has found a way to be victorious despite a multitude of technological advances. His rise to stardom began at the end of the low to no-flare urethane era, continued into the low-flare reactive era and today he’s a consistent threat in the high-flare reactive and particle era.

He has endured changes in not only equipment, but also in formats. He clearly dominated in the PBA’s old “marathon” 42 and 56 game formats, winning 33 times from 1986 to 2001. More recently, Williams also conquered the PBA’s new match play “sprint” format. When the PBA went to the match play format in the fall of 2001, he made the TV finals a tour-best seven times including a remarkable five straight. Some thought the new format would make it impossible for anyone to dominate, let alone have a TV streak like Williams put together. But his accomplishments again confirmed his greatness.

With all of Williams’ titles and the fact that he earned a degree in physics at Cal Poly-Pomona, you might think he’s an expert in taking advantage of today’s technologically-advanced bowling balls. Well, the opposite is actually true. Williams doesn’t really concern himself with exacting pin placements, extra holes, mass bias positions and CG placements.

Using either a ball company representative’s recommendations or a PBA player services rep’s input, Williams will simply drill a new ball and see what it does in relation to his other equipment. Because of his naturally straight type of shot, he normally uses layouts that will maximize a particular ball’s flare potential. He’ll then vary the cover stock by either sanding or polishing it to get the amount of friction that looks good to his eye and gives him the kind of carry he’s after.

Keep in mind that the number one influence in ball reaction is the aggressiveness and preparation of the cover stock. Therefore, all of today’s weight block technology and layouts can be wasted unless the cover stock matches up with a person’s particular style on a particular lane condition at a particular time.

During the fall of 2001, Williams used balls that had highly aggressive cover stocks with strong pin placements. The layout we saw him use most was one that placed the pin 3 3⁄4" from his positive axis point and positioned up toward his vertical axis line. For Williams, this layout produced a high amount of flare early and more of an “end over end” roll type reaction on the backend.

The oil patterns at the time were fairly flat and relatively on the short side. This layout gave Williams “a look” that for him was very readable and controllable on the backend, and therefore allowed him to put up some impressive numbers.

Like most of the top PBA players, Williams has a very basic grip. He uses a standard fingertip grip with Contour soft oval grips in both fingers. He uses no forward or reverse pitch in any of his gripping holes. The soft finger grips he uses “give me a tacky feel” for comfort. His thumbhole is a “Custom Thumb” mold which has an extreme amount of bevel; also done for comfort because of a pinched nerve he developed in his thumb in the early 1990s.

When a lot of bevel is used, it can make it difficult to hang onto the ball because there is less of a pressure point at the base of the thumb. Without these pressure points, excessive grip pressure would have to be used to simply hang onto the ball.

At the suggestion of ball rep Rick Benoit, Williams began using a cork thumb insert to provide a textured surface to solve that problem. The cork insert enables him to maintain a relaxed grip pressure which is essential to good bowling.

If your grip pressure is too excessive, it’s impossible to have a loose arm swing. Without a relatively loose arm swing, it’s very difficult to repeat shots because muscle tension is hard to repeat. Too much muscle in your swing also makes you lose “feel."

Gravity is a constant so work with gravity more and muscle less. If you use gravity as your friend, you’ll have a better chance of repeating your shots and increasing your scores and finishing better in your tournaments. If you’ve ever wondered how professional bowlers’ bowl 16 or more games per day, day after day, it’s because of good technique, being relaxed and letting the ball swing.

Williams’ record proves that no matter how unorthodox his style may look, one thing is certain: He knows how to repeat. And his repetition involves winning, and winning, and winning... ■BOWLING May 2002

PBA TECH TALK - Mika Koivuniemi

PBA TECH TALK with Ted Thompson

BOWLING Magazine March 2002

Reprinted with permission from the USBC

Koivuniemi combines International experience and American grip adjustments to compete on PBA Tour

When Mika Koivuniemi wins a tournament in the world of bowling, he wins big. In 1991 while still an amateur, Koivuniemi won the Federation Internationale des Quilleurs World Grand Masters. In 1997 he won the Super Hoinke for $100,000. After Koivuniemi turned professional in 1999, his first victory was in the 2000 American Bowling Congress Masters. In December, he added another of bowling’s most coveted crowns, the 2001 U.S. Open for another $100,000 first place check.

Those are good reasons to look at the tools Koivuniemi uses to conquer the tough conditions usually found in these major events. Koivuniemi grew up in Finland and therefore learned to bowl mostly in his homeland and Western Europe early in his career. There his game developed, like most of us, a style that enabled him to excel in the environment in which he was competing. The conditions over there, he said, “were one of extremes.” Either the lanes had very dry heads and tight back ends, or short oil patterns that made the ball hook almost uncontrollably. Koivuniemi therefore developed a style that had an excessive amount of loft built into his game.

This excessive lofting of the ball enabled his ball reaction (the hook) to be delayed, which worked well on both types of conditions that were prevalent in Europe. “It was normal for me to loft it as far as eight to 10 feet on a consistent basis,” Koivuniemi said. He also possesses the intangibles shared by most champions in all sports — excellent concentration and the ability to keep his emotions on an even keel, never getting overly excited or dejected. With strong physical and mental games, it’s no wonder Koivuniemi achieved world-class status in bowling before he joined the PBA Tour.

But the PBA Tour is a different animal. To continue the status he enjoyed worldwide, Koivuniemi soon realized a couple of adjustments were necessary to continue his road to success against “the world’s greatest bowlers.” On tour, one of the major challenges for most players is getting the ball to read the mid-lane and then continue its motion into the pocket with no violent reactions. This makes for a very readable ball reaction that is a necessity for consistency from pair to pair.

To achieve a more predictable ball reaction, Koivuniemi increased the reverse pitches in his finger holes to one-inch reverse. This is the most reverse pitch in the finger holes anyone on the PBA Tour uses today. It’s an attempt to get the ball off his fingers as fast as possible and onto the lane as quickly as possible. With this adjustment, Koivuniemi achieved a ball motion that reads the lane sooner with a less violent hook on the backend which is exactly the type of reaction a player needs to be consistent on the PBA Tour.

To continue the status he enjoyed worldwide, Koivuniemi soon realized a couple of adjustments were necessary to continue his road to success against ‘the world’s greatest bowlers.

Koivuniemi has a very high, loose arm swing which makes for fast ball speed. Again, that’s a product of the environment he grew up in and a challenge for him on heavily-oiled conditions. This is where specific ball choices and layouts come into play.

When the lane conditions are more on the higher friction side of the spectrum, Koivuniemi will use a ball that is reactive in nature only and stay away from the particle balls. He will use a layout that puts the pin 5 1/2" from his positive axis point and not use an extra hole. Both of these types of layouts help Koivuniemi keep the ball on line the majority of the time.

Koivuniemi would be considered a “Tweener” in today’s environment, someone who doesn’t go completely up the lane, but also prefers not to hook the ball across a lot of boards. With these changes combined with his natural game developed in Finland, Koivuniemi has proven himself to be a threat every week on the PBA Tour. ■ Bowling March 2002

PBA TECH TALK - Jason Couch

PBA TECH TALK by Ted Thompson

BOWLING Magazine January 2002

Reprinted with permission from the USBC

Forward Thumb Pitch helps Couch get a Better Grip on his Power

The grip of choice among most Professional Bowlers Association touring pros is a “relaxed fingertip grip,” one that lets the player release the ball in a number of ways. Release flexibility, in turn, allows them to fine tune their ball reactions to maximize scoring potential not only from week to week, but from pair to pair and even lane to lane.

Jason Couch is one of those “relaxed fingertip” players, but with an unusual twist. Couch incorporates what many bowlers would consider to be “excessive” forward pitch in his thumbhole. In the good old days, forward pitch in the thumbhole — where the hole is tilted toward the palm of the hand — was unheard of in most finger tip grips. Traditionally, most bowlers would use at least 1/4" to 3/8" reverse pitch to allow the thumb to exit the ball as fast as possible. The longer the span, the more reverse pitch was needed to enable the thumb to exit cleanly and impart “lift.”

The concept is simple: the earlier the thumb exits the ball, the longer it hangs on the fingers, creating lift which makes the ball react earlier. That trend has changed. Most top PBA players today use relaxed fingertip grips — typically 1/8" to 1/4" shorter than a full-tension fingertip — with zero or moderate forward pitch in the thumbhole. More lift is not a commodity today’s top pros want. Thus the trend is to get less lift from the fingers and in doing so helps the ball retain energy as it travels down the lane.

Jason Couch however, exceeds the norm. Up until the fall of 2000, he was using 7/16" forward pitch in his thumbhole. Because of his extremely high back swing, he creates a tremendous amount of gravitational force at the bottom of the swing and this amount of forward pitch was his way of not releasing the ball too early. Or in Jason’s words “dropping it at my toe.”

During the fall of 2000, some new irritation to his thumb began to develop and he felt a decrease in flexibility in his hand might be the cause. Another byproduct to his unusual amount of forward pitch was that he had to “pop” the ball off his hand at the bottom, making it hard for him to vary his rev rate which is a tool many of today’s pros use to combat the extreme variety of lane conditions.

Working with Couch, the PBA Player Services staff reduced his forward pitch to 3/16" and at the same time increased his span 1/8" on both fingers. By doing this, Couch still has that “locked on” feeling in the ball.

The end result was that he alleviated the irritation to his thumb, was able to roll out of the ball smoother at the release point and, at the same time, stay behind the ball a little more.

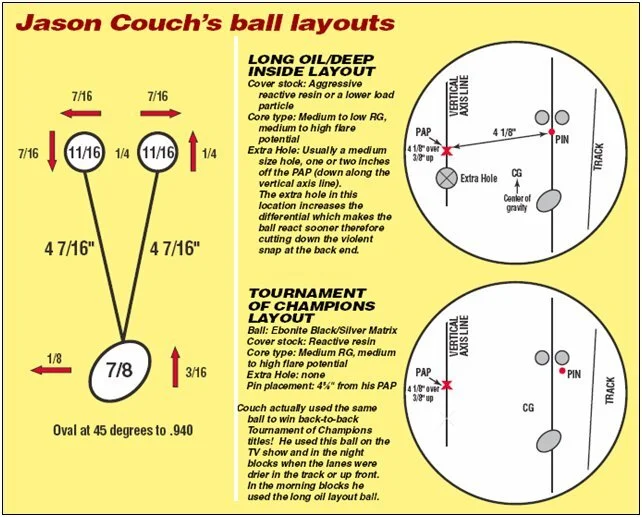

Layouts and ball choices

For the sake of simplicity, the PBA Tour uses three different lengths of oil patterns — short (less than 36 feet), medium (37-42 feet) and long (43 feet or more). Within these three patterns lie specific characteristics requiring any given player to make specific ball choices.

In 2001, Couch qualified second behind Parker Bohn III on a very short pattern at the Parker Bohn III Empire State Open in Albany, N.Y. It was a milestone accomplishment for Couch because shorter patterns (36 feet and less) have been his biggest challenge. His powerful release and high rev rate make his ball reaction violent and it’s difficult for him to control the pocket under those conditions. Compounding this was the fact that when he missed the pocket, the spares he had to try to convert were very difficult.

On shorter patterns the optimal place to play is usually the extreme outside line. A player must find a way to stay towards the outside portion of the lane and control their break point.

Couch did this during the PBIII Empire State Open by using a three-piece ball (pancake-shaped weight block) from game one. This type of ball has a very low differential value which means it has very little flare potential. In fact, during that tournament the PBA staff drilled him an identical ball later in the week because the first one became too “tracked up.” By using this type of ball, Couch was able to create a very consistent, controllable ball reaction throughout the whole week.

The medium-length patterns (37-42 feet) are the trickiest to play. Usually there is no defined place to play so the options vary greatly. Couch likes to attack these patterns with stronger reactive balls. He will also use layouts that put the pin in the ring finger area and depending on the amount of oil; he may or may not use an extra hole.

This enables Couch to create a breakpoint farther to the left than most other left-handers and therefore create area for himself by using the straighter players’ “carrydown” as hold area and fresher back ends to the left of that for swing area. His great shot-making ability is also a key in taking advantage of his power.

The longer patterns (43 feet and greater) tend to be Couch’s favorite. At the 2000 Brunswick World Tournament of Champions, the pattern was 50 feet long and played against the PBA Gold “Pro Pins” which weigh 3 lb. 10 oz. each. On such patterns, the ball simply doesn’t have enough time to hook a lot, so the place to play is usually more to the inside part of the lane. Couch plays the deep inside line as well as any left-hander since the powerful Steve Cook. With the heavier pins in play, it was no wonder Couch was victorious.

Couch’s ball of choice for this type of pattern is usually either a mild particle or strong reactive cover stock with the pin again around the ring finger area. The change he makes here is the extra hole placement, which is usually one to two inches below his positive axis point on his vertical axis line. This makes the ball react a little earlier and straighter into the pocket, which is imperative on these types of conditions.

Another advantage Couch creates on this type of pattern is that his lay down area is usually to the right of the right-handed players. He is then able to use the drier portion on the front part of the lane created by the right-handers as his “swing” area. Again because of his powerful release, Couch creates a much higher carry percentage than most players on this type of condition.

With the new “best-of-five” single-elimination match play format now being used on the PBA Tour, many of the high rev players struggled during the fall segment of 2001. The tour now bowls on freshly oiled lanes every round of the tournament, which historically has favored the medium to lower rev rate players. These types of players usually get a much smoother and more predictable ball reaction when the back ends are fresh (no oil carrydown).

Couch was one of those who struggled, but with his enormous talent and dedication to practice, you can bet it’s just a matter of time until he figures it out. When the tour resumes in January, don’t be surprised if Jason Couch becomes a major factor again. BOWLING January 2002

PBA TECH TALK - Chris Barnes

PBA TECH TALK by Ted Thompson

BOWLING Magazine November 2001

Reprinted with permission from the USBC

Barnes uses different grips on strike, spare balls to achieve a unique level of versatility

One of the most versatile players on the Professional Bowlers Association Tour today is 1998 Rookie of the Year, 2000 points and average champion and former TEAM USA member Chris Barnes. Barnes arrived on tour with a very impressive amateur resume. His start on the PBA Tour however, was more like a turbine engine. It started a little slow, but now appears to have kicked into full gear.

The reason for Barnes’ success is because he’s applying his full bag of versatile tricks. Barnes has demonstrated he can compete by playing the lanes very straight when needed, by hooking the ball a lot when needed, and by doing almost anything in between. It’s no wonder he made more PBA TV finals than anyone else in 2000.

Unfortunately, PBA history suggests that to become a consistent winner, a player must do something unique to gain that edge that results in many victories. It isn’t always advantageous to do a number of things well versus one thing great to be a star on the PBA Tour. However, if anybody can make versatility his friend, and start winning consistently in today’s environment, it’s Barnes.

Chris Barnes does one thing unique with his choice of grips. Yes, grips. He uses a certain grip for his strike balls and a different grip for his spare balls. His strike ball grip is tailored to be released in a number of ways. By using a semi-finger tip grip, he is able to roll out of it, hit it hard, or even spin it when the conditions call for it. Barnes uses 1⁄16" forward thumb pitch, which allows him to stay very relaxed with his grip pressure. This enables him to have great feel at the release point so he can throw the ball any way he sees fit.

Barnes’ spare ball is actually 5⁄16" longer in span (relaxed fingertip grip) and he increases his reverse pitch in his thumb. This allows him to break his wrist back to “kill” the amount of revolutions and allows him to stay behind it to make the ball roll more end-over-end. This grip and release technique limits the chance for the ball to change direction, which eliminates the chance of the lane coming into play. In shooting at most spares, that’s what the game is all about.

Barnes’ favorite layouts are much like most of today’s power players, leaning toward weaker pin placements and/or weaker weight blocks to control flair potential for maximum control. In PBA competition, hitting the pocket is never a given. The name of the game is control. Barnes has learned this philosophy very well over the last couple of years and the proof has been in his results.

One trick Barnes has used on occasion is trying to get his ball to “burn up” to control the pocket. This is done by using a ball with a strong core and strong cover stock so it will actually hook less on the backend to control the pocket. This combination takes a lot of knowledge and talent to work, and the player needs to know when to put it to rest.

One of Barnes’ strengths is playing the deep inside line. Barnes plays this line as well as anybody on the planet. His layout choice for a deep inside line is usually a 6" pin placement from his positive axis point (PAP) with the center of gravity “kicked out” just a bit, and no extra balance hole. Barnes also will choose balls with higher flare potentials and slightly weaker cover stocks. He uses this layout when there is a defined hook spot on the lanes, or when the lanes are a little more forgiving.

On very short patterns, or conditions where he has to play the extreme outside line, Barnes will also use a very weak pin placement and vary the strength of the cover stock depending on the amount of oil; the more oil, the stronger the cover stock.

When Barnes won his second PBA title in the 1998 Portland Open playing the 2 board (the original Cheetah pattern developed by Kegel), he used a pin 6 3/4" from his positive axis point, basically in his track. This put the weight block in a very stable position and took away all flare potential. This created a very predictable ball reaction and a straighter move into the pocket.

Barnes’ favorite layouts are much like most of today’s power players, leaning toward weaker pin placements and/or weaker weight blocks to control flair potential for maximum control.

On tougher lane conditions, or when there less of a defined hook spot, Barnes will choose equipment that has less flare potential. The differential Rg in these balls are usually .035 or less. He then strengthens the pin placements to 4 1⁄2" from his PAP and places an extra hole usually either on or slightly off his PAP. This, Barnes said, “creates more mid-lane reaction and makes the adjustment process more predictable.”

If the lanes have a lot of oil, he will choose a higher load particle ball and use a pin placement 5" from his PAP. Barnes likes to use larger extra holes in many layouts for balls for tougher lane patterns, lowering the RG (radius of gyration) value of a ball, which helps it rev up sooner. He can then be more aggressive with his ball speed. Since Barnes is one of the most intense competitors on tour, he can tend to get a little pumped up. That personality trait lends itself to higher ball speeds so the extra holes help keep the ball from over skidding and therefore reading the lane at a point that is more comfortable to his eye.

With his victory in the PBA Greater Nashville Open in October 2001, Barnes has now won three National Tour titles on three distinctively different lane conditions. His first title was in Erie Pa, on one of the highest PBA scoring environments ever. His second was in Portland Oregon playing the extreme outside line. In Nashville, he won on the challenging ABC 2:1 Ratio Sport Bowling condition under a new tournament format.

In my book, that’s the definition of versatility at the highest level and its talent that should keep Barnes on our picture tubes for years to come. ■ Bowling November 2001

PBA TECH TALK - Robert Smith

PBA TECH TALK by Ted Thompson

BOWLING Magazine September 2001

Reprinted with permission from the USBC

Welcome to the first “PBA Tech Talk,” a new series of columns by Professional Bowlers Association Players Services Director Ted Thompson. PBA Tech Talk will feature some of the PBA’s top stars and their tools of the trade — their grips, preferred ball layouts and types of ball decisions they make to combat the wide variety of lane conditions and environments they encounter on the PBA Tour.

How the ‘Sarge Easter Grip’ helped Robert Smith become a PBA champion

Robert Smith has one of the most explosive physical games ever seen in bowling. Walking through a bowling center, it isn’t uncommon to hear someone say, “Wow, did you see that?” If you’ve been around the Professional Bowlers Association Tour very much, you know the chances are pretty good that someone has just watched Smith destroy another rack of pins like only he can. Smith, who packs 215 pounds of muscle on his 5-foot-11 frame, creates a revolutions-per-minute rate and an entry angle that most bowlers can’t even dream of.

Early in his bowling career, when bowling balls were nothing like they are today, weight blocks with very little flare potential and cover stocks that weren’t nearly as aggressive as today’s served Smith well. The rapid advancement in bowling ball technology that has helped so many people around the world bowl higher scores, however, began to turn Smith’s bowling career into a nightmare.

Considered by many to be a blossoming superstar when he came out on tour in 1998, Smith finally headed home to California in late 1999 after two less-than-satisfactory tour seasons to search for answers. When the 2000 PBA season began, Smith returned to the tour with a new weapon, a grip known as the “Sarge Easter Grip.”

The Sarge Easter Grip — named for one used by the late American Bowling Congress Hall of Famer in the 1950s — is a conventional span on the ring finger and a fingertip span on the middle finger. Trying the grip was ABC Hall of Famer Barry Asher’s idea. Asher, who was recruited to bowl with Easter when he was 11, saw a photo of Smith on a Vise Inserts promotional poster and noticed Smith’s hand wasn’t open as much as other players.

Asher thought using the Sarge Easter Grip might weaken Smith’s grip, giving him more control. Ironically, Asher said Easter used to throw a backup ball, so he tried the grip to get a bit of side turn on the ball and wound up learning to hook it. Asher, who threw a spinner as an 11-year-old, used the grip to learn to stay behind the ball. Using this type of grip will greatly decrease the effect of the ring finger in the release. You’re really getting all the power from the middle finger, with the ring finger along for the ride.

The impact of Smith’s grip change was quickly apparent. He came back in a big way to win the 2000 U.S. Open followed by the Flagship Open in the fall. With his power harnessed by his modified grip, Smith believes he’s on his way to filling all those lofty expectations.

What was the change all about? With a full fingertip grip on both fingers, Smith created an extreme amount of revolutions and axis rotation. He felt as if his old grip was only allowing him to throw it one way — maximum hit.

The type of roll that was once such a huge advantage was now too difficult to control. “The original idea behind the grip change was to significantly cut the rev rate down,” Smith said, only to learn in CATS (Computer Aided Tracking System) testing that his rev rate dropped only 20 rpms, from 560 to 540.

Storm Products technical representative Steve Kloempken said the original goal wasn’t achieved, but the net objective was accomplished. “Robert’s ‘Sarge Easter’ grip has affected only one thing, his axis rotation,” Kloempken said. “His axis tilt has stayed the same. However, Robert’s direction of roll is unquestionably more forward.”

LAYOUT BASICS

On the PBA Tour, players face an infinite combination of ball reaction characteristics. Because of the different types of lane surfaces, amounts of oil, distances of oil, topography of individual lanes, temperature and humidity fluctuations players face on tour, they need to know when and how to use all their skills to compete at this highest of levels.

With the product line that most companies have today, a player can vary his/her reaction tremendously by using one “favorite layout” and drilling balls with different cover stock and/or weight block combination.

Smith’s benchmark drilling is a 6" pin from his positive axis point (PAP) with a strong mass bias and no extra hole. This layout places the pin over Smith’s middle finger and the center of gravity around the centerline of his grip. This layout cuts down on the flare potential of today’s highly dynamic bowling balls, giving him a much more controllable motion at the breakpoint as well as length.

On shorter oiled patterns, Smith will tweak the pin placement slightly toward the weaker side (6 1⁄4" from PAP) and use a ball that has less flare potential and weaker cover stock. For very long oil patterns, he will slightly strengthen the layout and often use a pin placement of 5 1⁄2" from his PAP. He will also select a ball with a more aggressive cover stock and higher flare potential core/weight block.

Technology and physical changes in the sport over the years have caused the end of many promising pro careers. To have a long and successful PBA career requires many skills. One of the most important is the ability to adapt to an ever-changing game.

Smith has proven he has the talent and mental toughness to adapt and become a champion. He spent part of the long summer break dominating the PBA Western Region, winning three titles in April alone. Only time will tell how many National titles are in his future. One thing’s for sure: he’s fun to watch. Bowling September 2001

The Cornerstone - Volume 1 - The President's Letter

The Foundation Newsletter - Summer 1998

What Happened?

The Crisis is upon us friends. Our sport is in trouble. Many of you that love the sport, as I do, will look at the Crisis like a friend who is in trouble and needs our help. We must not shrink from the task before us, we should welcome it. It is our generation that has been called to the challenge. If not now, when? If not us, who?

How did we come to this crossroad?

For as long as we have been using oil on bowling lanes, maybe even before, the relationship between the lane man and competitive bowlers has been strained at best. Why? Let me ask all of you a question. When was the last time a lane man told you he conditioned the lanes the same and you believed him?

Let me tell you my favorite analogy to explain the lane man`s dilemma. Imagine you are a lane man. Picture yourself standing on the lane. It is four o'clock in the morning a major competitive tournament begins at eight o`clock. You have all the latest machines to do the job. You have all the latest conditioners. What lane oil pattern will you use? How much oil will you use? You might look around for the book. There is no book. You might look around for the rules or guidelines. There are no rules or guidelines. Still, you must put something on the lane. So, you give it your best guess. By the way, we are getting real tired of guessing.

Sometimes it turns out fair and sometimes it does not. Why? Bowling is different now. The lanes are different, the balls are different, the styles are different, and the attitudes are different. The problems the lane man faces have grown to the impossible. There are no rules or standards. There is no balance in the bowling environment.

There is little record of all the tournaments of the past. Only Len Nicholson, Sam Baca, Lon Marshall, and the people who worked with them over the 27-year history of the PBA lane maintenance crew really know what happened with competitive bowling through those years. Hence my statement "Only the lane man knows for sure" is a true statement. What is wrong with this picture?

Before I met Len Nicholson in 1988, I knew that we had a real problem with lane conditioning. My work with scratch leagues as a mechanic/lane man in Phoenix, my work with bowling centers around the Midwest in the early eighties selling "The Key", and my experience as proprietor and manager of Kegel Lanes in Sebring had taught me that everyone was confounded about lane conditioning. Len taught me about the problems he had been facing with the PBA. The problems he was facing were much greater than what we, in the centers, were experiencing with league bowling.

I slowly came to the realization that if we didn't study lane conditioning as an industry, define the problem, test solutions, and implement the fix, then the sport and eventually the business of bowling could be in serious trouble.

That was 10 years ago. The lane-conditioning problem has grown to a big ugly monster that frustrates and infuriates almost everyone involved in bowling. The level of negativity in bowling centers has, at least, reached the level of the PBA in 1988. The negativity level in the PBA has continued to grow in those 10 years. Our heroes are losing hope. The credibility of Bowling as a sport in the US is virtually gone, both within and without the bowling community. How could this happen?

If we ourselves cannot lend credibility to our own events, how can we expect the rest of the world to respect our sport? Especially sponsors!

THE GREAT MYTH

As a bowler it is easy to think that if a lane is conditioned exactly the same, ball reaction will be the same. I only believed that until I actually tried. That trying took over 20 years and along the way we had to invent our own lane machines. It took many years just to find out the equipment of 20 years ago couldn't condition or clean two lanes the same in one day, let alone from day to day. During those 20 years the ball evolved, the lanes evolved.

The great myth about lane conditioning is that if you simply put down the same oil pattern that it will act the same day to day in tournaments or leagues. Most people believe this. I'm here to tell you it is simply not true. We still have not defined all of the factors that can cause ball reaction to change. To the uninformed and inexperienced it seems like a very simple chore. Maybe it used to be.

Herein lies one of the purposes of The Foundation. To pass on the experiences and the facts collected by our group. To put them into words in such a way that it can help each of you understand we are asking the same question we hear the most: "What happened?"

This information could help by giving you more knowledge about how lanes change and prepare you to make better adjustments. I hope it will help you accept change without filling your mind with negative thoughts about unfairness and unethical motivations.

THE TWO AREAS WE NEED TO STUDY: Technical and Social

The lane condition and scoring controversy can be broken down into two main fields for study. First the Technical problems involved in the bowling environment, that would include such things as: the machinery to perform the job, the oils and cleaners used, the procedures and coordination of the lane crew, the type of lane, the condition of the lane, the surface topography, kickbacks, flat gutters, pins, environmental factors, and bowling balls.

Most people believe that someone somewhere must be taking care of the sport of bowling. The ABC & WIBC test the new technology to be allowed into the game. The manufacturers must also be testing their products for bowling, right? Well, a few things slipped by. The bowling environment is way out of balance.

Since we didn't recognize the importance of lane care, we left the problems to a few isolated lane men. In fact all bowling centers were isolated, individual experiments. None of them had the resources needed to solve their problems. So, they would try all different kinds of things until the bowler complaints would quiet down. Proprietors were then blamed for creating high scores, bowlers accomplishments were turned down, and bowling writers cried for a return to integrity. We succeeded in creating a tremendous negative climate for social unrest and difference of opinion.

The social and psychological attitudes of the people in bowling, what everyone thinks about lane conditioning and scoring, is the second problem that needs to be studied. We have so many different kinds of games and attitudes; it is difficult to get a handle on what bowling really is anymore.

If we actually did solve the lane conditioning problems technically, no one would know, because we now have a monster social problem that could actually prevent implementation of any real fix.

Everyone must be able to see how fragile and unpredictable the bowling environment has become. A few of us have seen this coming for years. Too few understand it. Up until now our attempted explanations of the complexity of the modern ball, oil, and lane interactions have only been viewed as excuses, incompetence, or lies.

The truth is, we the bowling community can no longer afford to ignore this chore. We the lane men of this sport need help. Your first responsibility as a Foundation member is to stop gleaning the intent of any bowling event from the results.

What is "Process Verification" and Why do We do it?

There are four questions on the minds of competitive bowlers at every event in the world:

1. Who chose this condition?

2. What right did he or she have to do this?

3. What was the motivation of the person choosing?

4. Were the lanes conditioned the same from week-to-week, day-to-day, squad-to-squad, or was an adjustment made to change the outcome of the event?

It seems to me, that in order to make a dent in our psychological attitudes, these four questions need to be answered, and the answers need to be accepted.

For question number four we now have a solution. In the past, the lane maintenance person’s word has been questioned because of perceived changes in ball reaction. He/she never wins that one. We have found that there are many reasons why the lanes may be done the same, but ball reaction is different.

With the invention of Kegel’s Sanction Technology™, we can now prove the pattern is exactly the same every time. This is a huge step forward in understanding bowling's technical challenges because it eliminates the applied oil pattern as a variable.

Therefore, if the ball reaction is perceived by the players to have changed from the previous fresh condition, we can then look at variables other than the applied oil pattern.

When Kegel is in charge of conditioning the lanes for tournaments and events, we follow what we call the “Process Verification Procedure.” What this means is the process of cleaning and conditioning the lanes is verified. This ensures to the players that the same procedures are being followed each and every time we perform lane maintenance for an event.

Process Verification Procedure (PVP)

Inspection of the lane cleaning.

Ensure the oil program is correct in the lane machine computer.

Perform the oil calibration check. This is a procedure where the oil that would normally go onto the lane is captured into a graduated cylinder for exact measurement. The amount of oil is calculable and verifiable from the desired oil program.

Walking with the lane machine to ensure the machine operation is the same on each lane. This is done by looking at the valve time, the speed of the machine, and the total run time of each lane.

Look on each lane to make sure the oil pattern distance and the look of the oil pattern is the same on each lane.

Taking lane tapes at specific distances to make sure the lane machine applied the oil pattern as intended.

The tournament technical delegate/representative and lanes person then signs-off that nothing in the procedure has changed and is as intended.

By performing this procedure time after time, we not only protect the integrity of the lanes person, we also protect the integrity of the player, and most importantly as it relates to lane conditioning, the sport of bowling.